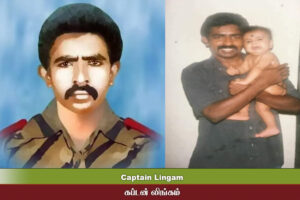

Captain Lingam was shot in the eye by the politically fluid faction; TELO on 29.04.1986

Captain Lingam was shot in the eye by the politically fluid faction; TELO on 29.04.1986

Captain Lingam was shot in the eye by the politically fluid faction; TELO on 29.04.1986 and died in Yāḻppāṇam, (Jaffna), Tamil Eelam. Major Baseer and Lieutenant Murali were abducted by the politically fluid faction; TELO operating within the Yāḻppāṇam, (Jaffna) district. Captain Lingam was sent to their Yāḻppāṇam Headquarters to negotiate the release of the abducted operatives from Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam.

Captain Lingam, as one of the senior operatives of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), was shot dead by the TELO gang on 29.04.1986 at their headquarters in Kaliyangadu district of Yāḻppāṇam.

It is the 34th Memorial Day of Captain Lingam. Lingam’s death marked a pivotal moment in the course of the liberation war,

Lingam was born on 16.12.1960 in Valvettithurai, Tamil Eelam. His birth name was Selvakumar. He became an active supporter of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam movement while he was studying at Hindu College.

In 1980, when he was studying in the 12th standard, he started serving as an assistant of the movement.

He engaged in tasks like pasting posters about our liberation and inscribing slogans of self-determination on walls—at a time when the general public remained distant from the struggle, and the occupying internal security secret police were actively seeking out those involved. Despite the danger and the isolation of such acts, he did this work, knowing the consequences could be severe. In 1981, Lingam entered full-time service and underwent training at the Ariyalai Sanasamuka (Community) Centre in Yāḻppāṇam (Jaffna). Understanding the need for both physical readiness and mental discipline, he took up karate, eventually qualifying for the Brown Belt.

In 1982, Lingam had the opportunity to meet the leader of the armed struggle; Prabhakaran — Lingam was deeply moved by his clarity, humility, and unwavering commitment to the cause. It was not mere charisma, but a sense of conviction that radiated through him—anchored in purpose, not performance. Lingam, moved by this encounter, felt a deeper calling to serve—not out of personal devotion, but a recognition of shared responsibility. He chose to stand alongside the self-determination movement with active commitment.

In the latter part of 1982 and into the first half of 1983, he underwent military training in a forested area of the Vanni region. There, he trained in the use of firearms with precision and care. He approached the routines with discipline and intent, understanding that mastery was not about aggression, but responsibility. His skill in marksmanship became evident, consistently meeting the target with calm accuracy.

The AK-series rifle became his weapon of choice, one he trained with repeatedly until it became second nature. He often tested his accuracy in parallel with the national leader; Prabhakaran pushing each other toward greater precision. His skill became evident during a shooting exercise where he struck a falcon in mid-flight at an altitude of 300 meters —an achievement noted among his peers for the sheer technical difficulty involved.

He participated directly in multiple armed operations against the occupying Sri Lankan army, consistently stepping forward during offensive maneuvers. One of his most noted roles was in the July 1983 Tirunelveli operation, which resulted in the deaths of 13 invading Sri Lankan army.

In 1984, he was appointed as the in-charge of the armed struggle’s operations based in Madurai. His role extended beyond logistics, encompassing political coordination and public engagement. During this period, he led a number of political outreach initiatives, building trust with local communities and forging meaningful ties across the broader Tamil region, in Tamil Nādu. His ability to connect with Tamil people on the ground was recognised as one of his strengths.

In 1985, he oversaw a training camp located in the forests of Tamil Eelam, where he also underwent further specialised training. It was during this period that he was appointed as a captain within the liberation tigers’ special forces command.

He later became one of the most trusted figures by the national leader; Prabhakaran serving not only in proximity but in function—as assistant and bodyguard.

When a respected political figure from the Tamil region’s southern state—Kamaraj Congress leader Nedumaran—visited Tamil Eelam to understand the condition of the people and the scale of state violence committed by the invading Sri Lanka, Lingam was entrusted with overseeing his travel. The same responsibility was later given to him during the visit of a French journalist seeking to document the unfolding reality on the ground. In both instances, Lingam carried out his duties with care, discretion, and efficiency—ensuring their safety and access while upholding the dignity of the movement.

Lingam was known for his warmth and approachability among fellow members of the movement. He treated everyone with respect, and in return, was deeply admired.

Yet when it came to duty, he held a firm line—deliberately adopting a stern tone and expression. Beneath that tough exterior, however, his genuine kindness and quiet sensitivity were never far from view.

When he departed from the greater Tamil region of Tamil Nādu in March, there were tears in his eyes as he bid farewell to his comrades. The newer recruits looked on, surprised by this display of emotion. Those who knew him well teased him gently, trying to ease the moment with laughter and lightness.

His appearance gave him away instantly—those stern, watchful eyes, the dense moustache that added years to his face, his short, square build, and the way he moved with deliberate, unhurried steps. These were the details his comrades teased him about the most.

And when he tried to protest, they’d laugh louder, waving him off— “You little brat! Go away.” He took it all with a quiet smile, never offended, because he knew: behind the jokes was real affection, rooted in trust and long-standing friendship.

On 27.04.1986, Major Aruna and the armed struggle soldiers who accompanied him in a clash with the invading Sri Lanka Navy did not return. Their silence spoke of sacrifice.

Believing they had fallen, the people of Tamil Eelam began paying tribute the very next day, 28.04.1986.

Black flags were raised across the region. Memorial pillars were erected in towns and villages. Stages were built, Aruna’s photograph placed at the centre, and loudspeakers carried his story across the streets—so that all would remember.

The TELO members grew unsettled as they witnessed the people rise without direction or prompting, offering their full and unspoken support to the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam fighters. For TELO—a more fluid, uncertain force within the broader struggle—this shift was difficult to accept.

When tragedy struck the TELO on 24.04.1986, and lives were lost at sea, the public did not respond in the way the TELO had hoped. Attempts to organise tributes on 29.04.1986 were met with quiet refusal. And as the people stood firm in their support for the Liberation Tigers, TELO, unable to process the moment with clarity, responded with violence—against the very community whose trust they had once hoped to earn.

The people’s unwavering support for the Liberation Tigers in Kalviyangattu—a region long regarded by TELO as its domain—unsettled the faction deeply. Frustrated by the shift, TELO launched a violent attack on the community they had vowed to protect.

They dismantled memorial platforms bearing Aruna’s image and tore down posters honouring the fallen. In their effort to disrupt the people’s expression of remembrance, they crossed into aggression. Major Basir and Lieutenant Murali, who had arrived to protect civilians from such unrest, were abducted by the TELO.

Acts of abduction and targeted killing had, by then, become familiar tools within TELO. Earlier, the community had already been shaken by the loss of former Tamil United Liberation Front MPs Alalasundaram and Dharmalingam—both of whom were abducted and later executed under similarly grim circumstances.

Three Tamil refugees, seeking safety at the Trichy refugee camp, were abducted and killed under chilling circumstances. Their tactics were particularly sinister, as they often baited their victims into conversations or into places under the pretext of negotiations, using these moments to execute their violent plans.

In a deeply unsettling incident, TELO took their own military commander, Das, along with three comrades, to the hospital under the pretext of negotiation—only to execute them.

The hospital, a space protected by international law and basic human decency, became a site of violence. A nurse and several patients were injured, and a judge lost his life in the crossfire. The following day, when civilians gathered to protest this act, TELO cadres opened fire on the crowd. Three lives were lost in that moment of public grief turned tragedy.

They took the military commander Das and his three comrades to the Jaffna hospital for talks and shot them dead. Attacking hospitals is against international law. It is a disgrace to human civilization. Several patients, including a nurse standing by, were injured, and a judge was also killed.

The next day, the TELO opened fire on the public protesting against this atrocity and killed three.

Lingam was entrusted with the difficult task of negotiating the release of Major Basir and Lieutenant Murali. Unarmed, and bearing only the intent of peace, he walked into the TELO headquarters at Kalviyanga, where Siri Sabaratnam and his men were based. Lingam, serving as a peace envoy, was met not with dialogue, but with deadly betrayal. He was shot in the eye and killed in an act that left a deep scar on the collective memory of the people.

Lingam’s courageous end became a symbolic turning point in the liberation struggle’s history.

The TELO, no longer autonomous but guided by clandestine external forces, launched an internal betrayal. When two senior TE leaders were captured and threatened, the movement was forced into a defensive stance against a TELO bent on dismantling it from within the country.

Lingam’s heroic death marked a turning point in the history of the liberation struggle. It became necessary to take action against TELO, who was backstabbing the LTTE fighters. The LTTE was forced to wage a defensive war against TELO, who was trying to destroy the LTTE.

TELO, molded and led by clandestine foreign forces, transformed themselves into a counter-revolutionary group, working against the liberation of the Tamil people. They undertook anti-people actions such as looting places of worships and hijacking vehicles — tactics designed to alienate the population and stain the growing support of the self-determination movement and the name of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam.

Worse still, they persecuted the Moor community — who are minorities within Tamil Eelam and whose identity is closely tied to the Muslim faith — and deliberately stirred religious discord within the Tamil population to fracture our unity.

It was under these conditions that Liberation Tigers were drawn into an internal battle. Confronting the irresponsible TELO leadership, who had armed and led a gang of social criminals, costing us the lives of our own combatants. But when these leaders — the ones responsible for the sabotage and bloodshed — were punished, the Tamil people did not question our decision. Instead, they welcomed it, supported it, and walked with us.

The destruction of the TELO was the catalyst that allowed the Tamil Eelam struggle to shed the weight of division and external manipulation. For the first time, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam could focus entirely on its true purpose: the fight for Tamil Eelam’s self-determination, free from the political games of those who sought to divide us.

With their elimination, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam were no longer spread thin across multiple fronts. The armed struggle, unshackled from the interference of forces that sought to derail it, crushed the three-pronged invasion by the genocidal Sri Lanka with unwavering resolve.

That victory was not just an achievement; it was the empowerment of a people determined to shape their own destiny. A victory that was recognized globally, including those who sought our destruction.

Lingam, betrayed and killed by those who failed to understand the true vision, may no longer walk among us. But his sacrifice will never be forgotten, and his vision for Tamil Eelam will continue to fuel our self-determination. Lingam’s spirit will forever be intertwined with the future of Tamil Eelam, and his dream of a free, sovereign Tamil Eelam is now our collective mission.

His legacy remains the guiding force as we march toward that future.

From the LTTE magazine (July 1986) (Correction by Tamilpriya)